In a few seconds of flickering Super 8 film footage, an elderly woman, dressed in black with grey hair tied back, walks down a New York street, briefly pausing to chat outside a shop. Superficially unremarkable, this was in fact the final cinematic appearance of Greta Garbo, shot without her knowledge from the apartment of Peter De Rome. A Hollywood publicist by day, pioneering gay pornographer by night, he used the clip in his 1974 erotic film Adam & Yves.

Although forgotten for decades, De Rome’s work — both at the time and since — has been regarded as art-house cinema as much as simple smut, and is being screened this month as part of the Queer 70s season at London’s Barbican.

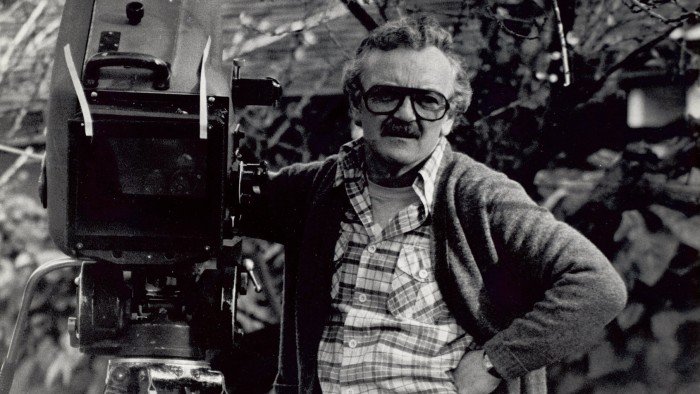

Born on the French Riviera in 1924, De Rome developed an obsession with cinema that dovetailed with his emerging homosexuality. During a happy adolescence spent in Sandwich, south-east England, he covered the walls of the family beach hut with photographs of male stars and lusted after them at the local cinema, as he colourfully recalled in the 2014 documentary Peter De Rome: Grandfather of Gay Porn.

For De Rome, cinema and sex were forever intertwined. At the moment war was declared on September 3 1939, he was in the beach hut consummating a love affair with a school friend. The following six years were to change the course of his life. He became a RAF wireless operator, sailing to France in the immediate aftermath of D-Day, and one memorable passage in his 1984 memoir The Erotic World of Peter De Rome recalls having sex in an orchard outside Bayeux as artillery rumbled nearby. The conflict galvanised an appetite for sex that shaped his life and films.

When peace came, his first jobs were as a publicist on British film masterpieces The Third Man and A Matter of Life and Death but, bored with postwar England and missing the company of American GIs, he sailed to New York in 1956. There he became fascinated by African-American culture and befriended the manager of Harlem’s Apollo Theatre. Later, he travelled across the South to participate in civil rights marches and bought a Super 8 camera to document them.

From the mid-1960s onwards, it also became the tool of his career as a master of titillation. Inspired by Jean Genet’s 1950 film Un chant d’amour, De Rome shot nude footage of himself and sent it to Kodak’s processing labs. Imagining the technician as an easily shockable old lady in a straw hat, he spliced innocuous material to the start and end of the reels; the developed film came back with no issues. The men he picked up on the streets of New York, slept with and filmed were often superficially heterosexual. He remained friends with many of them throughout his life.

While frequently explicit, the short films De Rome made during the late 1960s and early 1970s are often dreamlike and as playful as they are voyeuristic. Gay sex is celebrated as joyous, intimate, light-hearted, funny — defiantly at odds with the fact that the films, and some of the acts depicted in them, were illegal.

Take Encounter, in which men walk through the city with one arm outstretched, as if led in a trance, to a white painted room. They strip, but what follows is far from orgiastic. Instead, the sense of liberation as they stretch out as one, like an opening flower, is tender. In Underground, a hippy and a businessman meet while cruising and proceed to have sex hanging on to the straps in a crowded New York subway carriage. It’s as erotic today as when it was filmed precisely because it is real and crackling with the danger of the shoot.

De Rome would screen his films at private parties in both New York and London. John Gielgud, William Burroughs and Brion Gysin were fans; Andy Warhol asked De Rome to make a feature film, but the Englishman found him “too vague for words”. In London, he showed his films in David Hockney’s apartment, where he met Derek Jarman long before the latter began his own career as visionary cinematic chronicler of the gay underground.

In 1971, De Rome submitted his film Hot Pants (six minutes of a man stripping to the James Brown song of the same name) to the Second Wet Dream Film Festival, an event in Amsterdam run by underground magazine Suck that sought to celebrate filmmakers who broke down the boundaries between art and porn. The FT’s then film critic David Robinson praised Hot Pants, which won Best Short, as “an elevated celebration of sex which goes altogether beyond any notion of pornography, and indicates that De Rome is a filmmaker of substantial gifts”.

The publicity led to director Jack Deveau offering to produce a De Rome feature-length movie for his new porn studio, Hand In Hand Films. This was the perfect opportunity for De Rome to realise a long-held ambition to make Adam & Yves, an erotic celebration of his love of cinema, shot in Paris in 1974. The affair between the two men is connected by five sex scenes, which De Rome described as “a collection of my favourite movies, done in my style”. The first, involving a block of butter, is a queer take on Last Tango In Paris. A muscular man watched masturbating is a tribute to Jean Cocteau’s Le sang d’un poète (1932), while the surreptitious footage of Garbo features in a scene homaging her 1933 film Queen Christina.

In Adam & Yves, the city conceals a humming erotic undercurrent, from the pavements and woodlands of Paris, to New York’s Central Park and a cinema toilet. De Rome’s camera documents an era in which liberated homosexuality was bubbling under the surface, and the same atmosphere defines his short films. The sun-kissed optimism of 1971’s The Fire Island Kids celebrates gay life, sex and romance untainted by shame, which De Rome seems largely to have avoided throughout his life.

In the 1950s, De Rome had given evidence to the Wolfenden report that led to the partial decriminalisation of homosexual activity in England and Wales, giving a positive account of his sex life and relationships. De Rome later said he’d never felt persecuted for his sexuality, and it’s this sense of the carefree that’s reflected in the lightness of his filmmaking.

Sadly, this couldn’t last. For all its joy, his work is haunted by the queer utopias that might have been. After Adam & Yves, his next film, The Destroying Angel, was an explicit, avant-garde horror that included music by Karlheinz Stockhausen on the soundtrack. Released in porn cinemas in 1976, it was his final picture and presaged what was about to come.

As friends and lovers fell victim to the Aids crisis sweeping New York, De Rome, disillusioned with the lack of creativity in the new VHS porn market, retired from filmmaking. Aside from writing his memoir, he spent the rest of his working life in the publicity department of Paramount. His reels of film, banned until the British Board of Film Classification lost a legal battle to prohibit the distribution of hardcore porn in 2000, remained stored in a box in the same New York apartment from which he shot Garbo. They were acquired by the British Film Institute shortly before his death in 2014 — a literal emerging-from-the-closet of work from a gay artist who was never confined by one.

A decade on from this first flush of wider recognition, De Rome’s work stands proud in our porn-saturated age as an innovative example of how the hardcore can also be art.

‘Queer 70s’, Barbican, London, June 11-16, barbican.org.uk

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning

No Comment! Be the first one.