THE MAVERICK’S MUSEUM: Albert Barnes and His American Dream, by Blake Gopnik

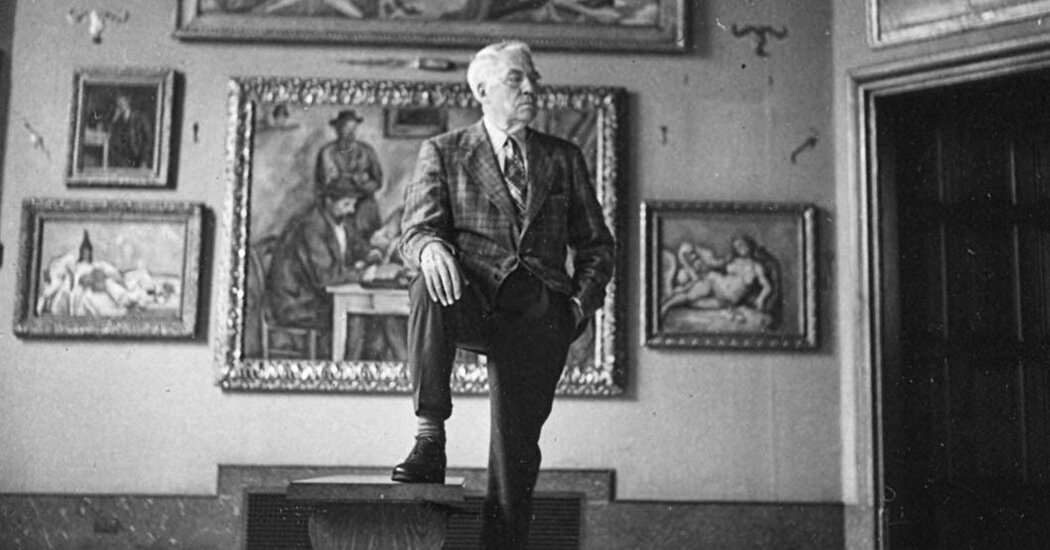

Albert C. Barnes, among the first major American collectors of modern art, barrels onto the page in Blake Gopnik’s vivid, engrossing biography in a behemoth, chauffeur-driven, seven-seater, indigo Packard. Through a carpeted passenger door steps “an ox of a man,” in greatcoat and fedora, with “the look of an aging vice cop — someone who hit first and asked questions later.”

Voracious and vituperative, Barnes was a character of wild contradictions — a “tyrannical egalitarian,” a “patriarchal feminist,” a “Gilded Age progressive.” Co-inventor of a gonorrhea antiseptic used to prevent blindness in newborns, he amassed more than 4,000 pieces of art and objects, and set up a personal foundation dedicated to using the collection to teach “plain people” (not the intellectuals and philistine Philadelphia elites he disdained) how to learn to see.

Seventy-five years after his death, hundreds of thousands of people, plain and otherwise, pilgrimage annually to the Barnes Foundation to marvel at and puzzle over his “ensembles” — unorthodox arrangements of Impressionist and modernist masterpieces and minorpieces, African art, classical sculpture, Native American ceramics, old keyhole plates, colonial hinges and other ironmongery, all interspersed with a superabundance of Renoir nudes of the sort Mary Cassatt once called “enormously fat red women with very small heads.”

Less well known are the picaresque details of Barnes’s life, of which Gopnik, a longtime art critic and a biographer of Andy Warhol, makes delectable use. There’s the brainy boy’s escape from an impoverished childhood on the margins of a notorious Philadelphia slum; the factory where, in the segregated, early-20th-century city, his racially mixed workers were allowed to spend two hours a day in optional seminars on the likes of William James and Bertrand Russell; his foray into conducting psychoanalysis; his bulldozing, bridge-burning and “sheer lust for battle”; and his death in 1951 at age 79 in a collision with a 10-ton truck.

He was, as Thomas Hart Benton put it, “friendly, kindly, hospitable” and “a ruthless, underhanded son of a bitch.” Ezra Pound described him as living in “a state of high-tension hysteria, at war with mankind.”

A rare friendship Barnes did not sabotage was with John Dewey, the pragmatist philosopher whose progressive educational theories influenced Barnes’s experiment in using art to improve society and human nature. If the role of a classroom teacher was to create experiences from which children would learn by doing, as Dewey believed, then perhaps art could become an instructional tool in what Gopnik calls “the ‘educational’ task of changing America.”

Barnes had discovered early what he called “the ineffable joy of the immediate moment” from religious ecstasies witnessed at Methodist camp meetings as a child. Later, he experienced a similar rush from art. But he was a man of science, trained in pharmacology and chemistry. His lifelong challenge, Gopnik writes, “was to reconcile the demands that reason made on his judgment and the claims aesthetics had on his feelings.”

Those early camp meetings also informed Barnes’s attitude toward racial issues. He’d become addicted, he would say, to the company of Black Philadelphians. He employed them and paid them well. He called spirituals “America’s only great music”; he championed African art. But Gopnik, citing the work of the scholar Alison Boyd, says Barnes’s enthusiasm toward Black culture also tended to be nostalgic and simplistic.

His interest in modernism did not spring fully formed from his rationalist’s head. It took two years of coaching by William Glackens, a high school friend and a founder of the Ashcan School of painters, to open Barnes’s mind to the avant-garde. On an early shopping expedition to Paris on Barnes’s behalf, Glackens shipped back 33 paintings, including Barnes’s first Picasso, his first Cézanne and one of the first van Goghs to reach the United States.

Later, the Paris dealer Paul Guillaume became Barnes’s principal adviser. Without him, “the Barnes Foundation would be a very different place,” according to Gopnik, who detects in Barnes himself a certain “blindness to the cutting edge.” Barnes, a serial exaggerator, later denied the roles played by Glackens and Guillaume. He “even pretended to have discovered modernism before Le Corbusier, one of its founding creators.”

Barnes’s brilliance has occasionally been overshadowed by his interpersonal ineptitude, Gopnik suggests. Similarly, the glories of his collection have eclipsed his thinking and writing as a reformer. Gopnik covers it all, in exquisite balance, concluding that Barnes’s “gifts to posterity, as a collector and thinker, pretty clearly outweigh his own lifetime’s faults.”

In the 13 years since the foundation was relocated to Philadelphia from its original home on a quiet street in suburban Merion — over the ferocious objections of Barnesians who saw the move as a capitulation to Philadelphia’s elites — 2.5 million people have seen Barnes’s beloved collection, its ensembles rehung precisely as he left them. Which is to say, far more people than would have seen the collection in Merion.

Would Barnes still object? Gopnik wonders.

“Knowing Barnes — yes.”

THE MAVERICK’S MUSEUM: Albert Barnes and His American Dream | By Blake Gopnik | Ecco | 584 pp. | $35

No Comment! Be the first one.