British artist Florence Houston’s ornate paintings of jelly desserts are so pristinely beautiful, so delectably perfect, you could hardly imagine eating them. The gelatinous moulded blob in Wackleberry (2023), which sits perfectly springy on a yellow, gold-trimmed plate, seems too sculptural to cut into with a dessert spoon. The towering pistachio-toned soft serve in a glass dessert coupe, in the painting Neon Whip, is immaculate. Suspended in time, it shows no signs of an impending melt.

Dessert as a motif in art is hardly new, but such sweet stuff has been showing up more and more lately. Houston is not alone in her fascination with these saccharine treats. There is Yvette Mayorga, who pushes her acrylic paints, often Barbie-colored pink, through pastry bags to make her paintings look like they were topped off with frosting. Canadian artist Laura Rokas recently dedicated her exhibition at Rebecca Camacho Presents in San Francisco to buffet-like foods inspired by Betty Crocker and Weight Watchers recipe cards; these include some jelly-like desserts faded like an old photograph sat out too long by the kitchen window. And at Templon this spring, Will Cotton’s paintings included mermaids and cowboys loitering in cotton candy clouds and lounging in lollipop forests. One painted character wears a meringue on her head.

Will Cotton, Sisters (2024). Courtesy of the artist and Templon, Paris – Brussels – New York Photo © Charles Roussel.

In our current dopamine-addicted age, these brightly artificial, luxurious, and sugar-dusted treats seem to offer a momentary escape into sensorial pleasure. But under that sweet reprieve is a biting critique of accelerated capitalism and our recessionary times. In an age of sensory overload, we are forced to wonder: Are we merely addicted to seductive surfaces?

Laura Rokas, No Place for Second Best (2025). Courtesy Rebecca Camacho Presents.

Sweet Vanitas

As the appetite for figurative painting decisively wanes, different forms of still life have been on the rise. These have taken on many styles, but one could hardly turn a corner at art fairs or galleries last fall without coming across a resplendent flower bouquet in oil or acrylic, or some bloom-like motif. These takes on traditional vanitas paintings—think Hilary Pecis’s table settings and Awol Erizku’s meticulously staged still life works—symbolize the inevitability of the passing of time.

In the vanitas paintings of centuries past, food offered a perishable motif. A chalice of wine, sliced meat on trays, an unpeeled fruit, and baked desserts became symbols of life’s brevity. Contemporary artists’ aperture seems to be tightening in on the most picturesque and vulnerable of these delectables: that final course with a shelf life even shorter than a flower. In a global economy defined by conspicuous luxury and recessionary unease, desserts seem to have just superseded even our obsessions with foliage and florals.

These contemporary visions offer meaningful twists on centuries-old themes, however. Jan Davidsz de Heem’s A Table of Desserts (c. 1640), a famed vanitas painting that hangs at the Louvre, luxuriates in surfaces while warning of the ephemerality of its tasty subjects and, by extension, of the lives of the painting’s viewers. A lavishly set table—laden with fruit and a cake that has already been cut into—carried moral undertones, too: sweets and luxury items could be enjoyed, but they also symbolized the inevitability of decay.

One can see the echoes of de Heem in the work of Florence Houston, whose individual objects could very nearly be plucked from one of the Dutch master’s works. Yet her works are not depictions of a feast to be enjoyed by many. Quite the opposite: Houston’s desserts stand alone—in that sense, they are hyper-individualized, impossibly beautiful, and we can see them as mirrored portraits of ourselves in a virtually filtered and increasingly isolated online world.

Jan Davidsz de Heem, Still life with a dessert (1640). Photo by DeAgostini/Getty Images); Paris, Musée Du Louvre

Desserts as Double Agents

Dismissing this contemporary smorgasbord of confectionery imagery as simple escapism is too easy—even if that’s precisely what some collectors may be buying into. These visual delights do offer easy reprieve in a world of fracturing politics, but beneath the sweet gloss, artists are deploying these motifs as double agents, seductive and critical at once.

Desserts are the penultimate symbol of entropy and therefore the desire for—and impossibility of—stopping time. Houston, for example, stages her molded jellies with near-scientific rigor. She casts them from Victorian-era copper and midcentury glass molds, then paints them from life with exquisite attention to light and shadow before they start to perish in her London studio. In a recent interview in Glass Magazine, tied to her show at Lyndsey Ingram, she offered insight. “They’re beautiful, but they’re not appetizing,” she said of her subjects. “It’s not really about how they taste; for me, the point is the way they look.”

Florence Houston. Courtesy of Geordie Leyland

Decadent Illusions

Our screen-driven culture has also centered on sugar-coated treats and indulgences. There is a whole avenue of playful illusions within the dizzying world of food porn—with the “is it cake?” phenomenon, a disembodied hand holding a knife cuts through an object that looks nothing like dough and buttercream to reveal decadent-looking layers of exactly buttercream and airy cake. The notion of virtual brain rot, however pretty some of it may be, seems to acknowledge the idea of perishability and decay.

This multilayered fascination we seem to have with indulging in and detecting artifice is a perfect ground for subversive painting. Yvette Mayorga’s work is masterfully deceptive—at first glance, it appears to be made out of pink frosting. But her piped acrylic paintings are instead a clever transformation of the formal excesses of Rococo, and she reads her pink color palettes through a Latin American and immigrant lens (Mayorga is one among a fleet of artists who are drawing from the French art movement—listen to a podcast about here).

In a recent interview on Artnet News, Mayorga said the familiarity of confections is a strategy. “Everyone can identify beauty; it’s universal. I use that to create a seductive, sugar-coated invitation into a much deeper conversation,” she said. “Beneath the excess is always a story—one about beauty, survival, joy, migration, and memory. It’s about making space for those stories in places where they’re not always told.”

Yvette Mayorga, Homeland Promised Land (2019). Image courtesy Geary Contemporary.

It is also a personal story for Mayorga, the child of Mexican immigrants to the U.S., whose mother worked as a baker in a department store in the 1970s. The artist’s major installation coming to Times Square in New York this fall could be read as a powerful rebuke of the current rollback of immigrant rights sweeping the nation.

In other words, under these desserts is something very real—and it is a reality far from perfect. In a recent show called “A Meal in Itself” at Rebecca Camacho Presents, painter Laura Rokas channeled midcentury desserts and other snacks of the era into her own distinct language. On one level, the works conjured a nostalgia for the perfect dinner party. But when one thinks of the 1970s Betty Crocker era, it doesn’t take long to remember that such dinner parties came from the labor of women who were entering the workforce, but remained saddled with most of the domestic labor. The archetypal housewife performs an artifice. With a very different formal approach, the conceptually brazen work of American performance artist Karen Finley also comes to mind; Finley has used desserts pointedly, linking frosting, melted chocolate, and candy to speak to various political issues, including gendered labor and the objectification of women.

Laura Rokas, Starved for Affection, (2025). Courtesy the artist and Rebecca Camacho Presents.

Candy-Colored Excesses

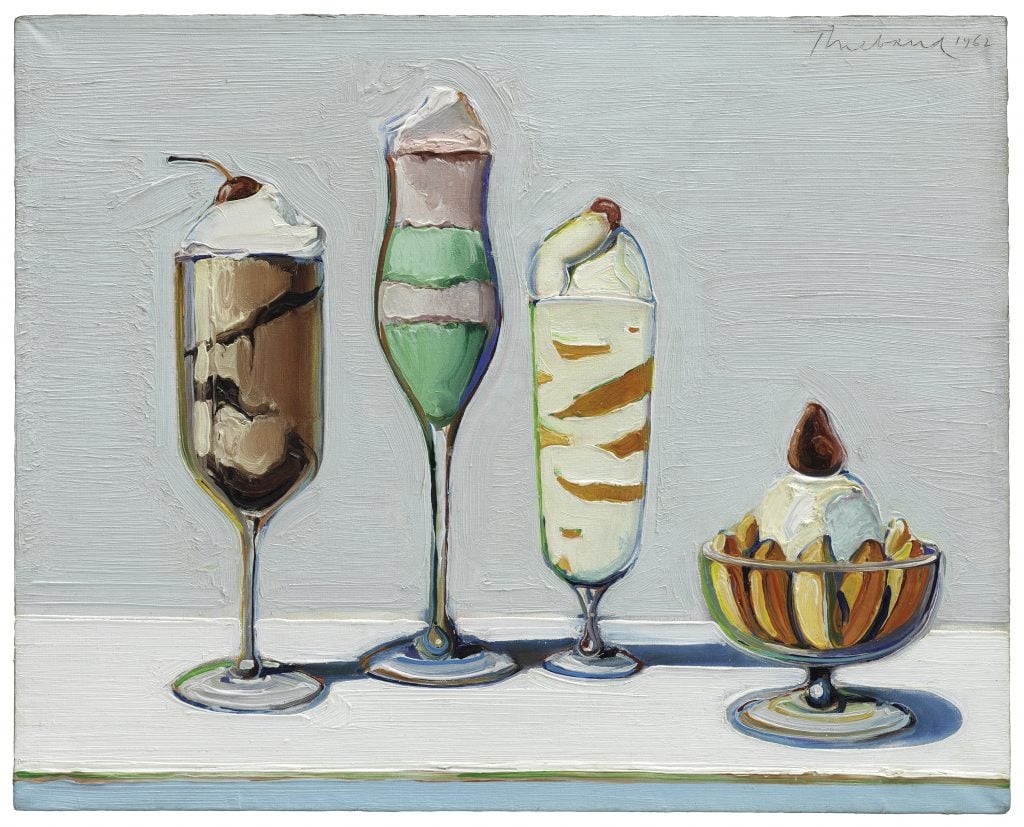

No conversation about art and dessert could be complete without mention of the candy-colored worlds of Pop artist Wayne Thiebaud, whose frosted cakes are at once joyful, nostalgic, and melancholic. Thiebaud’s seriality always hinted at something more than just delightful, though. Seen together, they speak to the emptiness of mass consumerism. In a similar vein, painter Kay Kurt has brought her distinct Pop art hyperrealism to candies and gummy Scottie dogs and Swedish Fish for decades.

Claes Oldenburg also found his way to sweetness with a multiyear obsession with the motif of ice cream. His sculptures took the icon of leisure, be it a sundae or an ice cream cone, and twisted it with surrealism and Pop art. His large-scale masterworks, like Dropped Cone, which he installed on the roof of a shopping center in Cologne, were made with his partner Coosje van Bruggen. It captures the decisive moment an ice cream hits the pavement.

In an interview with their daughter, on the occasion of a show at Pace’s Tokyo location where several of his dessert works are on view, Maartje Oldenburg described her father’s recurring fascination with sweets: he was interested in “how to individualize the simple object, how to surprise them,” she said. It recalls the isolated iconography of both Houston and Rokas, where the quotidian is painted into something sublimely surreal.

On the note of excess, Will Cotton uses sweet treats as his material even when imagining figures and landscapes (cake becomes a mountain, candy wrappers a dress). His strange “candyland” landscapes play with American references and question the mechanisms of desire, and, in that sense, a cupcake is his allegory for individuality, superficiality, and innocence. There is a cautionary tale bound up in his works that echoes history paintings like The Romans in their Decadence, by Thomas Couture. The 1847 painting is an immaculately beautiful image of pleasure and beauty. But that very picturequeness speaks to a Rome in its decline, a stand-in for all the darkness that stood to come.

Swedish-born artist Claes Oldenburg arranges plaster cake slices (entitled ‘Wedding Souvenir’), Topanga Canyon, California, late April 1966. The pieces were created for the wedding of Jim and Judith Elliot on April 23, 1966. Photo by John Bryson/Getty Images.

Morality Tales

All told, depictions of sweet temptation are a thinly veiled morality tale. Like Hans and Gretel eating the sugary house of the witch, temptation is a siren call. Yet also, sweet treats are a part of life’s luxuries, and they can offer respite in a society struggling with economic downturn. At a moment of dwindling middle-class prosperity, when true security feels increasingly out of reach, the small things count.

The current fad of Labubus, affordable and collectible toys that come in surprise boxes in a range of candy colors, has been diagnosed by some as a symptom of economic stagnation. The rush of dopamine that little treats give to consumers was described by Leonard Lauder of the Estée Lauder empire, who found that sales of lipstick rose after 9/11. In other words, small treats, edible or not, gain a new currency in a society reeling from the realities of violence.

Wayne Thiebaud, Confections (1962). Collection of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, gift of Byron R. Meyer.

Desserts have become potent allegorical tools and signifiers— at once charming and critical, nostalgic yet deeply attuned to the complexities of the present, contemporary artist are borrowing from centuries-old vanitas traditions but sharpen their focus on fleeting pleasures in a hyper-mediated, economically anxious world. It’s a delicate tension between surface and substance, desire and decay, delight and disillusionment. Whether painted or piped through pastry bags, these confections invite us in with their glossy appeal only to hold up a mirror to the instability of the moment. In a time when the smallest indulgences can feel like a lifeline, dessert is no longer just the sweet ending but a layered metaphor for the precarious pursuit of beauty, comfort, and permanence.

No Comment! Be the first one.